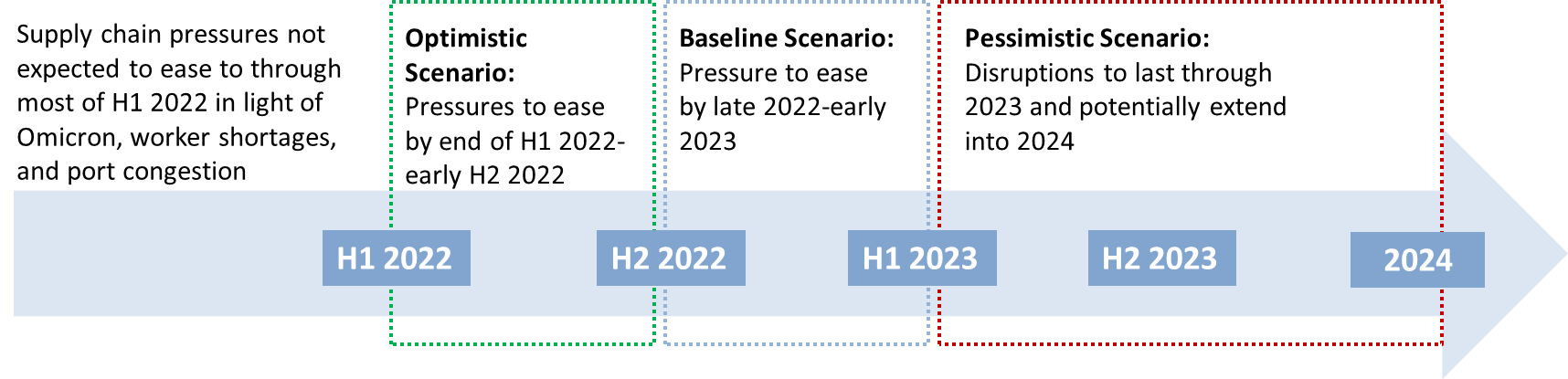

Supply-side disruptions, along with factors such as new variants and surging inflation, recently led to a downgrade in Frost & Sullivan’s 2022 global growth forecast from over 5% to 4.5%. Easing of supply chain pressures by late 2022-early 2023 is anticipated under a baseline scenario. Businesses will increasingly incorporate just-in-case strategies as opposed to just-in-time manufacturing in order to improve supply chain resilience.

How did the Supply Chain Crisis Unfold?

While the world economy was slowly recovering from the onset of the pandemic and lockdowns, it found itself grappling with another issue; supply chain disruptions. Shortages of products from computer chips to lumber have been restraining industry growth and global economic recovery.

How did the crisis unfold?

The easing of lockdowns, e-commerce growth and generous stimulus support contributed to a demand boom, while producers struggled to ramp-up capacity following pandemic closures and logistic bottlenecks. As a reaction to shortages, pre-orders in larger quantities became evident, exerting further supply-side strain. Region-specific factors have also intensified the situation. For example, Brexit-related new customs procedures and worker shortages disrupted UK supply-chains, while power outages in China caused a further snag.

Scenario Outcomes- What can Businesses Anticipate Moving Forward?

Supply chain pressures will most likely continue for the most part of 2022, as represented above in the baseline scenario, with easing beginning by late 2022-early 2023. However, there are various push and pull factors, which in isolation or in tandem with other factors, can enable speedier fading-out of disruptions or further extend the crisis. Key factors have been examined below:

Easing Consumer Demand: With the world economy entering year two of recovery in 2022, some easing in demand-side pressure is expected, especially in light of rollback of fiscal stimulus and monetary policy support. Multiple interest rate hikes in countries such as the US and UK will especially help keep demand in check.

Chip Production Increase: While there will continue to be supply-demand mismatches, shortages should begin easing by H1 2023 with higher semiconductor production coming online. Consequently, manufacturers of cars and consumer electronics and other chip-reliant industries will be able boost production and improve time-to-delivery.

Risk of New Variants and More Virus Waves: This is the single biggest risk factor which can prolong the supply crisis. Emergence of fast-spreading variants and resultant restrictive measures would restrain factory production, increase worker shortages in warehousing and trucking, as well as cause trade delays.

China’s Zero-COVID Policy: As a global manufacturing hub, China’s sustained zero tolerance approach of immediate, tight lockdowns and strict quarantine conditions can cause adverse ripple-effects for global supply chains and hinder recovery.

Geopolitical Pressures: A potential reduction or cut-off in Russian gas to Europe, in response to sanctions over possible Ukraine invasion, would escalate Europe’s energy crisis, hindering industrial production. The UK’s possible exit from the Brexit’s Northern Ireland protocols risk UK-EU trade wars.

Implications for Households, Businesses, and Governments

Household Cost of Living Pressures; Cutback in Discretionary Spending: Supply chain snags, higher food and energy prices and other factors will fuel inflationary pressures, possibly prompting central banks to bring forward or pursue more aggressive rate hikes. Consequently, home, car and personal loans would become costlier. Higher priced essentials, as a result of the disruptions, would also force consumers to reduce discretionary expenses on entertainment services and dining-out.

Reduced Reliance on Just-in-Time Manufacturing Model; Digitization and Automation of Supply Chains: Brexit caused an evaluation of the just-in-time model (lean inventory, low wastage) across the EU and the UK as goods could no longer be seamlessly transported across borders. The susceptibility of this lean manufacturing model was further highlighted during the pandemic. Firms will increasingly balance just-in-time versus just-in-case strategies (higher safety stock, supplier and production diversification) for improved supply chain resilience. AI-driven, digital supply chains will be critical in navigating input and labour shortages and mitigating risks.

Increased Government Policy Support for Localization and Strategic Industries: In the earlier stages of the pandemic, governments had announced policy initiatives to secure supply chains. Japan, for example, extended incentives for Japanese companies to relocate production from China back to Japan or other select Asian locations. Amidst ongoing chip shortages, governments are seen to be extending a host of incentives to fortify domestic production. The US House of Representatives, for example, recently passed a $52 billion subsidy and grant scheme for chip manufacturing (enactment pending), while South Korea has announced $451 billion in chips until 2030. More global government schemes can be expected to help strengthen local manufacturing capabilities and reshore high-tech and vital supply chains.

In summary, securing global supply chains will be critical in alleviating inflationary pressures, driving industrial growth, and improving global economic prospects. Supply-side recovery becomes all the more important given the high exposure to downturn for contact-intensive services in the event of potential new variants. While multiple stakeholders collectively work towards restoring supply chains, businesses will engage in revamping supply chain strategies to prioritize risk management, while maintaining the drive for cost reduction and efficiency.