Increased geopolitical uncertainty and threat scenario has resulted in nations spending more on their defence preparedness. SIPRI has reported defence spending at USD 1.98 billion in 2020 which is 2.6% above that of 2019. The increase has come even though there has been a significant slowdown of the global economy in addition to trillions of dollars being pumped for fiscal stimulus and healthcare measures.

The trend bodes well for the defence industry, and especially UAVs as the customers look to acquire low-cost operational capability against the increased internal and external threats. The low-cost life cycle of UAVs coupled with an increase in operational capability due to technological advances in Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance (ISR), Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning ( ML) will increase the adoption of UAVs in the next decade. In East Europe [1], the trend is even more significant with increasing allocation to military UAVs.

Frost & Sullivan has a well-defined framework for identifying regions that have the market potential for the adoption of a particular military solution. While the framework is applicable for all weapon systems and regions, this paper explains the military UAV market opportunity in Eastern Europe based on the identified factors.

The framework is based on a weighted average of :

Let us consider the factors one by one taking examples of military UAVs in Eastern Europe:

- Defence Budget: Spurred by the increase in geopolitical uncertainty and NATO mandate of spending at least 2.5% of GDP on defence, the combined defence spending of the East European countries rose to USD 43.49 billion in 2020 up by 8.6% from 2019 spending of USD 40.1 billion. The increase signifies the greater willingness to spend on defence even in an economically challenged environment. At the same time, the total defence spending is low and hence will favour the acquisition of UAVs for offensive and ISR roles rather than the more costly assets such as fighter aircraft and special mission aircraft. A case in point being Azerbaijan which largely depended on Turkey supplied armed drones to gain a decisive advantage over Armenia in 2019.

- Threat Landscape: The primary external threat to these countries emerges from a belligerent Russia. The Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the ensuing conflict with Ukraine is a prime example of this threat. Additionally, most Eastern European countries also list internal unrest and terrorism as major security threats. Russia is a major military power, and none of these countries can hope to match its military might which actually makes UAVs, especially armed (including loitering munitions) and ISR UAVs, more practical. For e.g., it is opined that Ukraine’s best bet is to detect any offensive Russian movement (say a tank attack) early and keep the threat at bay by using offensive drones while it signals for help from NATO/ other international agencies.

- Level of Organisation/ Technical Change Required to Adopt UAVs: Incorporation of any weapon system requires organisational and technical change for deployment and integration in the concept of operations. Armed forces which have the organisational structure and technical procedures in place are likely to have a higher adoption rate. A case in point is Czechia, which recently raised a UAV battalion and signifies that the country has the necessary structure in place for incorporating UAVs

- Customer Need Recognition: The country may not recognise the need for a weapon system in the context of the threat landscape or the capability which the system can endow. This factor is low for the Eastern European countries, however, Hungary is one example. It has a more central location which makes it relatively safer than Ukraine which borders Russia and also lack active UAV programs in the country. The possible way into such markets is by increasing customer awareness

- Defence Procurement Process: Market attractiveness is highly influenced by the seller’s ability to negotiate the defence procurement conditions and procedures. The overall result is a combination of different consideration such as the complexity of the procedures, the knowledge of the procedure, past relationship both at the company and national level, sanctions etc. Most east European countries have a low history of cancelling defence deals and relatively simple procedure; however, a few problems do exist. For e.g. both Poland and Romania have had past history of cancelling UAV acquisition programs due to change in policy or charges of favouritism.

- Competitive Landscape: The probability of a win in any market depends on a combination of the overall competitive landscape including indigenous capability. Poland has significant indigenous capability in light and medium UAVs which would render the market unattractive for foreign OEMs. It does not have the capability in heavy-armed UAVs, and this could have been an opportunity however it has already announced that it would either consider General Atomics MQ 9 B or Elbit Hermes 900 for the role thus shutting the door for any other aspirant. On the other hand, Hungary does not have any indigenous capability in the military and would be amenable to a foreign offering. The offering could be in the form of a sale or joint development in view of the failed attempts to launch an indigenous military UAV program.

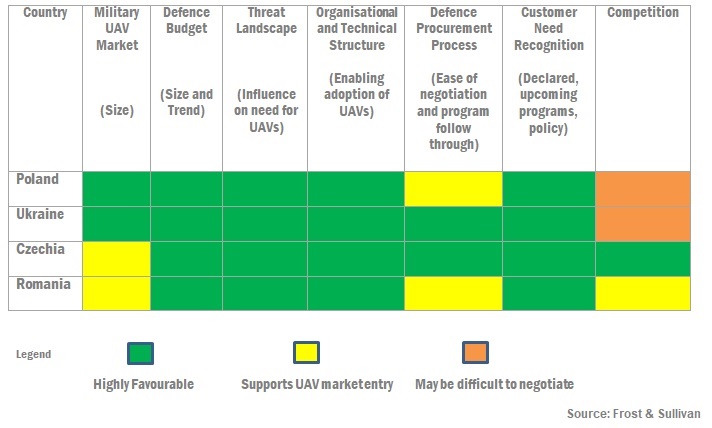

The Eastern European countries are a mix of mature and upcoming markets for the adoption of military UAVs. Major growth drivers are the need for UAV solution based on the threat landscape, low overall defence budget which precludes the acquisition of costlier assets and yet an increasing willingness to spend on defence as observed by the rise in outlay. The heat map of the opportunity matrix for a few highlighted countries is as below:

The total East Europe market is estimated at USD 300 million with a CAGR of 15% for the next 5 years. Poland, Ukraine, Czechia, Romania, Hungary, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia are the top markets followed closely by the rest of the region.